Introduction

About 14 months ago, Accuweather extended its long-range forecasting to 25 days. Forecasters at the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang and at the independent Phillyweather.net both expressed significant skepticism that any forecast could be accurate at that distance. Tom from Phillyweather.net ran a small sample, confirming his impressions.

About 6 months ago, I also ran a small sample test. I collected 25 days worth of Accuweather’s forecasts for a single future day, comparing them to each other and then to the final weather for that day. The forecasts weren’t that great, as I expected. But again, this wasn’t much of a sample size. I wanted to go bigger. Now, over 6 months after my last post, I now have data comprising all of (astronomical) winter and spring, and it’s time to see the results.

Methodology

Every day since November 16, 2012, at approximately 6:00am, I have retrieved accuweather.com’s forecast for zip code 19103 in Philadelphia. Using a custom script, I capture, process, and store the forecast high and low temperatures, amount of precipitation and (in winter months) snow forecast, and a brief text description of the weather that day. This data is retrieved from the forecast web site, the same as if any person looked up the forecast. I also retrieve the actual weather for the previous day. I therefore have partial data (less than 25 forecasts) for days through December 9, 2012, and complete data starting 25 days after the first forecast retrieval, on December 10. The data in this post is based on 195 forecast days, consisting of all days from December 10, 2012 through June 22, 2013. This includes all of astronomical winter and spring, plus a bit of fall. (Or, if you prefer, most of meteorological winter, all of spring, and a few weeks of summer.)

On some winter days, where a given day is much colder than the previous day, Philadelphia has a “midnight high”. (It might be the case that January 11 has a high of 45 degrees, it has cooled down to 35 by 12:01am on January 12, and the afternoon “high”, or local temperature maximum, is only 33 on the afternoon of the 12th.) In these cases, it’s not fair to punish a forecaster for a forecast of 33, which is 2 degrees lower than the true high, but which is a more useful forecast to a consumer using the website at 6:00am than the already-past high of 35 would be. Therefore, I’ve attempted to manually adjust the “actual” high temperatures where possible, but I’m sure I didn’t catch all the midnight highs.

In some cases, due to technical difficulties, the data retrieval was done after 6:00am but before 3:00pm. This happened less than 2% of the time.

All of my averages are means, though I acknowledge that medians might be a better indicator of accuracy in some cases.

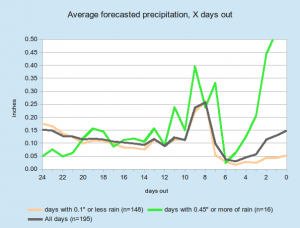

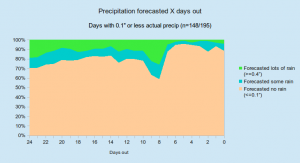

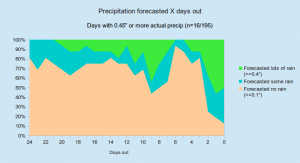

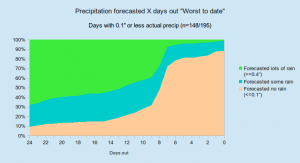

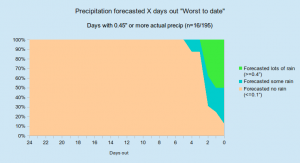

I treat one-tenth of an inch of rain, or less, as equivalent to no rain. (However, I never use this equivalence to hurt the forecaster; it can only help them.) Similarly, over four-tenths of an inch of rain in a day is my threshold for “a lot of rain”. I did not attempt to grade precipitation forecasts for days on which between 0.1″ and 0.4″ of precipitation ended up actually falling.

An aside: “worst to date”

If you have an outdoor wedding on June 2, and the forecast for that day as of 16 days prior is 88 degrees and sunny, and it ends up being 88 degrees and sunny, is that a good forecast? Did Accuweather nail it 16 days out?

I would argue that the answer is “maybe”. It depends on what the intervening forecasts are. If the next day, 15 days out, the forecast for the 2nd is 71 degrees and rainy, then I would argue that both forecasts are bad. The 16-day-out forecast provides the happy couple no reassurance, because the very next day they’re stuck buying some large white umbrellas. To me, the value of a forecast is inherently tied to how consistent it remains.

Seen differently, a forecaster could “game the system” by providing wild guesses of 3 or 4 different weather pictures on the 3 or 4 most distant days of every forecast. That way, one of them is bound to be right, and the forecaster can claim that they got every day right somewhere more than 3 weeks distant!

To mitigate this, I have created a metric that, for want of a better name, I call “worst to date”. You may prefer to think of it as “worst reverse to date” if that helps you (though it doesn’t help me).

The idea is that I penalize the forecaster for the worst forecast made in the final X days before the forecast day. If the final 10 days of a forecast are relatively accurate, but day 11 is way off, then the forecaster cannot get credit on days 12 through 25 for any forecast better than the poor day-11 forecast. (The time you spent not buying umbrellas is not worth anything to you if you still have to scramble to buy umbrellas later.) This ends up creating a monotonic function: the most distant forecast is always the worst (or tied for worst), and the day-of forecast is always best (or tied for best). The forecaster can only do well, starting from any given day in advance, by being both accurate and consistent from that point forward.

I attempt to be clear throughout this analysis when I am using “worst to date”, and when I am relying on the raw forecast data. Sometimes “16 days out” really does mean the forecast made exactly 16 days prior, and sometimes it refers to the worst of the final 16 days’ forecasts. I hope it’s obvious which I mean when.

When I present an average of “worst to date” information, I first take the worst-to-date for each individual day’s forecast, and then average the results.

Getting to the point

OK, enough introduction. Now to to the point: Are the 25-day forecasts any good?

In a word, no.

Specifically, after running this data, I would not trust a forecast high temperature more than a week out. I’d rather look at the normal (historical average) temperature for that day than the forecast. Similarly, I would not even look at a precipitation forecast more than 6 days in advance, and I wouldn’t start to trust it for anything important until about 3 days ahead of time.

Here are some numbers:

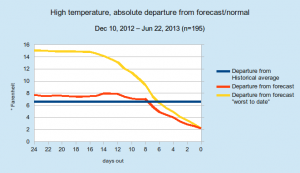

- In a statistically significant (95% confidence) sense, a forecast 11 days out or more is worse than simply looking at historical average high temperatures. A forecast 8, 9, or 10 days out is not conclusively worse than the historical average, but it’s not better either.

- Over my sample, the actual high temperatures were an average of 6.6 degrees off from the historical average high temperatures. The Accuweather forecasts 8 days out were an average of 7.5 degrees off. 7 days out, they were an average of 5.8 degrees off.

- At some point during the 10 days leading up to any given forecast day, on average, there was a forecast high as bad as 11.4 degrees off. (That is, the “worst-to-date” average for 10 days out was 11.4 degrees off.)

- For any given day that ended up not raining, more often than not, there was at least one forecast issued in the previous 13 days for that day which predicted a lot of rain.

- With the caveat that I had a relatively small sample size of days when it rained a lot (only 16 of them), there are many forecast “distances” for which a lot of rain was predicted as often for dry days as for rainy ones. (To cherry-pick an egregious example, 6 days before a dry day, the forecast was dry 95% of the time. 6 days before a rainy day, the forecast was dry 94% of the time.)

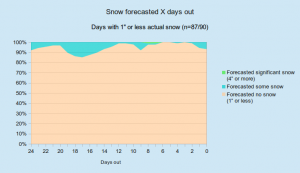

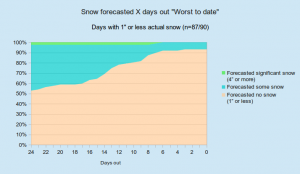

- It did not snow much this winter in Philly. 87 of the 90 winter days (December 21 through March 20) had an inch or less of snow, and we never got more than an inch and a half in the other 3 days. However, 45% of those 87 not-snowy-at-all winter days had at least one forecast issued for them calling for more than an inch of snow!

Graphs

Now for the fun part. Graphs!

Here’s a comparison between using historical averages and Accuweather forecasts to determine the high temperature:

This graph shows pretty clearly that things are pretty consistently bad until about a week before the target date:

Enough about high temperatures, since really, precipitation is more important. This chart shows how precipitation forecasts evolve for an average rainy day as compared to an average dry day, and how late they diverge:

Here are two charts showing what percentage of the time a dry vs. rainy day is forecast when the day ends up dry, and when the day ends up rainy:

And here are the “worst-to-date” versions of those same charts. In this case, the rainiest forecast is considered the worst for days that end up dry, and the driest forecast is considered the worst for days that end up rainy.

I think this last chart is the most egregious example. It’s only about 2 days out from a rainy day that you really start to get consistently rainy forecasts, on average.

Finally, though I hope to get better snow-forecast data in coming years, especially for days when it actually ends up snowing a lot, here’s what I have for winter days that don’t end up with much snowfall:

And the “worst to date” version:

In this relatively dry and snowless winter, I think snow forecasting was Accuweather’s strength. Out of 2250 (90*25) snow forecasts, only 2 were over 4 inches, and the only late “bust” was on March 6th. The March 5th forecast predicted 3.8 inches, which was revised down to 2.5 on the morning of the 6th, and only a trace ended up falling.

Conclusions

I’m not a meteorologist or a statistician. While I like to fake being both, the reality is that all I’m doing is moving numbers and data around. In particular, on the meteorological side, I’m lost when it comes to reading actual weather models. I would say that I’d leave that to the professionals; however, after running this data, I don’t have much faith in them either.

This information can’t possibly be news to the Accuweather meteorologists, who I assume are quite skilled at not only reading weather models, but also understanding them well enough to know when their outputted data is suspect. I can only imagine what conversations happened between those meteorologists and Accuweather’s business interests, in advance of this product being launched. And I wonder what it currently means for Accuweather’s bottom line, now that they can claim to having the longest-range forecasts in the business. I can only assume that it helps them, though I don’t think it’s helping their customers.

Instead, I prefer to put my trust into the bloggers and hobbyists. Tom and his crew at Phillyweather.net, and the Capital Weather Gang, are all well-written weather aficionados. They all know their stuff when it comes to model reading and forecasting (most or all of them have formal training in atmospheric and meteorological sciences), and they also know and will happily share with you information about the limitations of the science of meteorology. Since they’re not trying to sell anything, I’m buying. If you’re not in Philly or DC, I recommend you look for something similar in your neck of the woods.

Failing that, I am hereby announcing Josh Rosenberg’s 180-day forecast product! Here’s how it works: Any time within 180 days of the day in question, look up the historical average high temperature. That’s my forecast high for the day. I guarantee it will be more accurate than Accuweather’s, beyond the 10 day mark, or your money back. (As for a precipitation forecast: Around this part of the world, it’ll probably rain a bit. But not too much.)

That’s all I’ve got. I welcome all comments and corrections. I especially welcome more formal statistical analyses from those with statistical training, as well as any comments from meteorologists. Raw data is available upon request, either if you want to do your own analysis, or if you’re just curious how bad the forecasts were in advance of some particular day in the past 6 months. And finally, thanks for reading.

UPDATE: It has come to my attention that last month, Accuweather extended their long-range forecast to 30 rather than 25 days. Commentary on this is left to the reader.

Super awesome. I’m totally on board with the worst-to-date metric.

I like your example wedding date :)

I never understood why the useless weather people hold a job despite being wrong all the time. Only profession where you so inaccurate and still pull in a good paycheck. I am hopeful that one day they will be able to predict the daily forecast with accuracy and leave the long range to the experts.

You think it’s maybe indeed a “long rage” (sic) forecast. I mean, how long can anyone stay angry. Seriously, what a fun column.

Ha. I proofread this post multiple times, but apparently never the title. Thanks for the catch; typo fixed.

Good review! Accuweather managers may know little about meteorology and deterministic chaos. But they probably know enough about marketing and human irrationality.

Great post! Check out http://www.weatherist.com. They do a lot of work on forecast accuracy.

Pingback: Is this the Worst Winter Ever? - Page 6

Pingback: How accurate are weather forecasts? | News

Pingback: The accuracy of long range weather forecasts | Greendale Weather

Nice article!! For my wedding day, July 12th, it has said sunny and 85, cloudy and 92, and now thunderstorms and 98, all within a weeks span. This is still 2 weeks away! Accuweather can’t be trusted, but it is humorous and entertaining!

Thanks. That’s much appreciated. I’m a researcher myself (psychology) and so I enjoyed your thoughts about methodology. I’m in melbourne australia trying to predict a good day for a public indigenous tree planting day. Appreciate the wake up call.

Pingback: How to Read Weather Forecasts During Snow Season | The Inertia

Awesome Read. Very interesting loved the statistics. From my own experience i totaly agree with your conclusions.

Forecasts like this can be very helpful for people like me who want to travel in November, yet I plow snow. I noticed this month all in the 40s and 50s. Whether or not it’s clear doesn’t matter to me. I only want to know if it will be cold enough to snow.

You do not have to go 25 days. Sometime the weather forecast changes every day. So it is ridiculous to thing that Accuweather and predict the weather for 25 days out. If the weather is crucial for travel I check periodically and that still does not guarantee an accurate weather report.

A famous Portland Oregon meteorologist when asked what the public wanted in their forecast replied a seven day forecast. Knowing full well that the best Portland can do with the ocean, the mountains and the gorge in our neighborhood was 3 days out. He obliged knowing that the other four days were phony. Near the end of his career the public was sampled again for what they wanted. 10 days. Give us a 10 day forecast. OK he said. And proceeded to give them their 10-day funny forecast. Wise meteorologist that he was, he knew that no one lofted weather balloons from out in the Pacific to gather forecast data. 3 days out was the best we could “see” from Portland. Meteorologists in New York however didn’t have to be top shelf. All they had to do was call up the Ohio people overhead and ask them what was happening, and Viola! An easy 7 day forecast.

BS in meteorology ’74, MS in environmental engineering ’78, both from Penn State (the school that most AccuWeather forecasters attended. That being said, weather forecasts more than 5 days out are worthless, and even the 4th and 5th day are of questionable value. I don’t know how these private forecasting services ever get clients. Perhaps gullibility runs rampant these days.

Yeah, I am laughing all over when I read about this long range ‘fony phorecasting stuff. Here here for Env Engeers!! These are some of the rare people that are expansively trained to understand more aspects of Climate Ch than anyone else hardly. Meteorologists being no intellectual slouches – they have a nuanced science for sure. But fun tho. It’s one of the few sciences that can keep on teaching, without blackboards, power points, laboratories, equipment, or sensors. just eyes – but It doesn’t quite come up to Env Eng in my take.

Helpful article! Accuweather is predicting thunderstorms on a day we’re planning a party, more than a month away. I’m going to choose not to worry about it> : )

It is amazing what people will take as “fact.” For that reason, forecasts should be accompanied by a “degree of confidence” to let everyone know whether the weather is a true forecast, an historic average, or a dart.

Greetings Josh Rosenberg!

All that useful information being said, can you recommend a good weather app for my android phone? I’ve had the Accuweather app on it, and have family in three different parts of the country, and I check on their weather. Accuweather’s forecasts have been WAY OFF so many times in their region, it’s laughable!

So what’s your reccomendation?

Thanks for the great article!

Barb

I have noticed that lately accuweather forecasts are not accurate at all like they used to be yrs ago, what has happened?, this morning I dialed it up on my phone and it showed that it was raining, uh, skies were blue. I need a new accurate weather forecasting online station.

it is now a 3 month forecast…

ridiculous. They claim 9 rainy days including today feb 20th (which is raining) until may 18th, 2017.yeah let’s see that one pan out…

I love your worst-to-date method! Genius.

I liked the author’s conclusions, where he talks about the contradictions between professional interests and business interests. That’s right: there is a clear discrepancy here.

I can confirm this with my own studies of the accuracy of weather forecasts:

http://en.weath-forec-acc.pp.ua/

http://weath-forec-acc.pp.ua/forecast

https://weath-forec-acc.herokuapp.com

The main conclusion is this: beyond the 10-12 day period, no one can predict better than climatic (historical).

If people value their reputation, they will not give a forecast for 20, 30 or more days. The oldest, and one of the most accurate meteorological services, the English MetOffice, is limited to a forecast of only 6 days.

Accuweather.com forecasts are now for 90 days! But this is not the limit: Metcheck.com – 6 months! Needless to say about the value of these forecasts.

Thanks to the author for interesting materials.